Proffers are a big and important part of federal criminal defense practice. Basically, it involves a defendant, a witness, a person of interest, or a person with information having a face-to-face meeting with a prosecutor and law enforcement agents while accompanied by an attorney. (Attorneys can also have “attorney proffers” whereby the attorney tells the prosecutor what his client would say if the client were to hypothetically have a proffer with them).

Proffers can be done for many reasons: to initiate cooperation agreements, to attempt to persuade a prosecutor of one’s innocence, to offer information for an investigation, or to seek leniency at sentencing. Regardless of the reason, however, they should never be undertaken lightly.

First and foremost, a person proffering to federal law enforcement cannot lie. Obviously, if law enforcement discovers that the person has lied during a proffer, then that person’s credibility will be destroyed. Thus, any hope for a cooperation agreement or mitigation at sentencing will be eliminated. There are two other equally important reasons, however. First, a lie during a proffer can be prosecuted potentially as a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001, which makes it a federal crime to lie to a law enforcement officer. This is typically why prosecutors bring law enforcement agents (FBI, Homeland Security, etc.) to the proffers. Similarly, a lie during a proffer session can result in an enhanced sentence for any related convictions, under the theory that the lie “obstructed justice.” Finally, a lie during a proffer session could invalidate the proffer agreement, which otherwise protects a person from having those statements during the proffer session used against them.

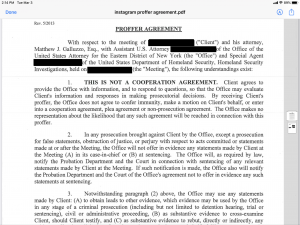

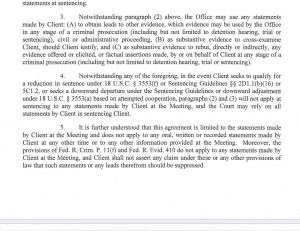

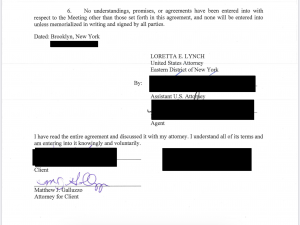

Prior to doing a federal proffer, a person typically signs a “proffer agreement” like the one attached here. As you can see, it makes the statements “off the record” for the person talking to law enforcement. Basically, the prosecutor promises not to use any of the person’s statements against them on their direct case in the grand jury or at trial. There are some important exceptions, however. First, if the person lies during the proffer, then the entire promise is invalidated. Second, the prosecutor can use the information obtained during the proffer to find other evidence. Third, the prosecutor can cross-examine the person later with their statements should the person change their story at trial, for example.

Before doing a proffer, the attorney representing the person should understand everything and anything that the person might say. Thus, a practice proffer is a very good idea prior to walking into the real one. Moreover, the prosecutor should carefully consider the bigger picture from the prosecutor’s perspective: what does the prosecutor likely know, and what is the prosecutor trying to discover or accomplish with the investigation? Understanding how prosecutors think is critically important for defense attorneys representing people in federal proffers.

If you or a loved one have been asked to speak with law enforcement about a crime or investigation, it is critical that you retain experienced counsel to assist you. Matthew Galluzzo is a former Manhattan prosecutor who has represented numerous people who have proffered with law enforcement, and has been able to use those proffers to his clients’ advantage on many occasions.